Bringing to Life Danjuro VIII: Prints by U. Kunisada

February 4, 2022 - April 16, 2022

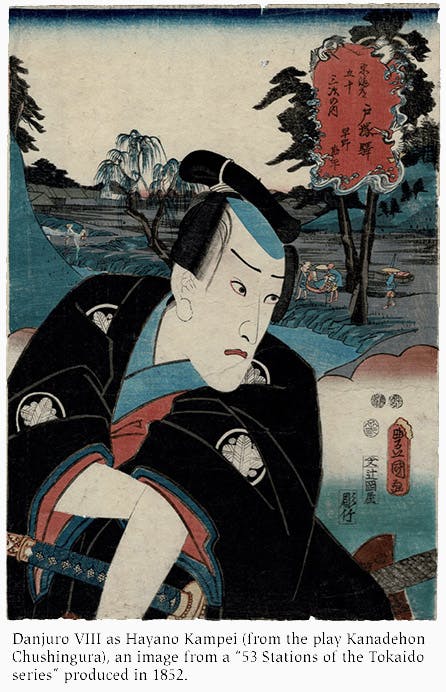

This exhibit explores depictions of one of Japan's most famous kabuki actors, Danjuro VIII ((1823 - 1854), by Japan's most prolific and successful (in his own lifetime) ukiyo-e print designer, Utagawa Kunisada (1786 - 1865). Its focus is Kunisada's portrayals of Danjuro VIII in 5 plays in which Danjuro played leading roles between 1851 and 1854.

Danjuro VIII (1823 - 1854) was a member of the Ichikawa family lineage of kabuki actors (a lineage continuing today in the person of Ebizo XI, see below) in Edo (now modern day Tokyo). The eldest son of Danjuro VII (1791 - 1859) and a direct descendant of Danjuro I (who began the lineage in 1675), Danjuro VIII started acting alongside his father at age 7. At age 9 he took on the Danjuro name from his father. Father and son performed together until, in the fall of 1854, Danjuro VIII took his own life while the two were on tour in Osaka.

The lineage continues. In 1985 Ebizo X took on the name of Danjuro XII and championed it until his death in 2013. He is followed by his son Ebizo XI. The subject of a recent CBS 60-minutes documentary episode (12.27.2020), Ebizo XI is a major force in kabuki theater today. Ebizo XI had planned to take on the name of Danjuro XIII in 2020, but postponed because of the Covid hiatus.

Learn more about Ebizo XI.

Five Plays of Ichikawa Danjuro VIII

As a print-maker using the Japanese color woodblock method, I find it a wonderful opportunity to be able to see, touch and hold prints that were made during the heyday of this art form, the ukiyo-e period of the mid-19th century in Japan. Kunisada's yakusha-e (prints that depict the actors and moments of the kabuki theater world of Edo) is the focus of my collecting. It is Kunisada's sense for dramatic pictorial structures that I am most interested in and I find Kunisada's yakusha-e prints utilize his most dynamic compositions.

Kunisada's depictions of Danjuro VIII are exceptional and they likely exceed in quantity his portrayal of any other actor. What made this actor so interesting to Kunisada? Was Kunisada mostly responding to a keen public interest in images of this popular actor? Was Kunisada especially drawn to the drama of the young man's acting career? Kunisada was good friends with Danjuro's father, Danjuro VII. Was Kunisada, in collaboration with Danjuro VII, partially responsible for Danjuro VIII's fame and fate?

In sharing these prints I seek to immerse in the world of mid 19th century Edo, Japan. The high-point of Danjuro VIII's short career coincided with the arrival of Admiral Perry's ships in 1853 which led to the end of the Tokugawa regime, the Edo period, and Japan's 250-year isolation from the rest of the world. Why this focus on prints of that particular time? I have above alluded to two central reasons: the drama of this one actor's career and the dramatic aspect of these particular prints which depict that actor. But another reason is that I have been able to obtain these prints. Two interesting facts explain why such sophisticated art from 170 years ago is available and affordable.

- Kunisada was an exceptionally prolific participant in what was a very productive art industry (the ukiyo-e woodblock print-making of 19th century Edo, at the time the largest and most literate city in the world). In his lifetime Kunisada was the most popular and successful of all the ukiyo-e print designers. He made the most prints, he had the most students. What is a lot? Boston's MFA museum has in its collection over 10,000 prints designed by U. Kunisada. That is a lot.

- Until recently Kunisada's work was largely overlooked by Western ukiyo-e art historians. Dismissed as “decadent" and an example of the decline of the art form in the middle of the 19th century, until Sebastian Izzard's 1993 publication of “Kunisada and His World" no books dedicated to Kunisada's work had been written in English. Only recently have art historians and enthusiasts such as Sarah Thompson, Andreas Marks, Horst Graebner (with his comprehensive web-site kunisada.de), begun to make organizing inroads onto the looming mountain of Kunisada's art.

Yakusha-e prints illustrate a fascinating symbiosis between the world of kabuki theater and the world of the woodblock print-making. In the city of Edo these two art industries flourished together, achieving commercial success through a mutual inter-dependence. Prints functioned as advertisements and as souvenir materials for the plays and their production coincided with the performances of the plays. The plays gave the prints a world of stories to describe. Hundreds of actors and supporting staff were likely employed in the theaters, thousands were employed in the production of the prints. The woodblock prints were one of the major exports of Edo, at the time perhaps the world's largest and most literate city. At the time of their manufacture these prints would have been distributed throughout Japan. When Westerners began to arrive after the Meiji restoration of 1868, they were carried to Europe and the U.S. and their influence on artists and art-forms continued, affecting significantly 19th and early 29th century art traditions such as Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, the turn-of-the-century Arts and Crafts movement in England and the US, art traditions such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco.

It is useful to remember that though the print designs were directed by the imagination and brush of Kunisada, these prints were created by teams of designers, carvers, printers, and publishers working collaboratively. Print manufacture was the result of the interactive work of many players: publishers who undertook the financing of the print production and likely handled their distribution, carvers who refined and gave life to the lines and patterns of the artists' brush work, printers who worked out the application of colors. Also important to the existence of these prints was the print-buying public. In the case of Kunisada's prints the designing was also collaborative. Kunisada ran a design shop with many apprentices, in many (perhaps all) of the prints of this exhibition there is present the hand of other artists' brush-work adding in aspects of the designs (the fulfillment of patterns, likely much of the calligraphy, often the landscapes of the backgrounds). This was a world in which, like the theater world of the actors these prints depict, opportunities to explore rich interactions of shape, color, pattern, and story abounded. Much of the formal language was connected to the fabric industry, prints would employ patterns and color combinations of newly developed clothing styles. Easily mounted on screens or collected in albums, folders or just piles of printed papers, yakusha-e was, and is, imagery that offers insight into the highly sophisticated visual aspirations of Edo in its heyday. These prints depict an imagined theater realm that didn't end at the close of the performances. The drama of the actors, the lure of the costumes, Kunisada's depiction of the theater spaces, all these aspects of the theater live on in these prints. I am fascinated by these prints as evidence of prodigious quantities of highly skilled hours of collaborative designing, carving and printing, seeing and imagining.

Kunisada seemingly reveled in the complex world creating this imagery. His ability to coordinate his brush-work with others to produce thousands of prints, books, and paintings is astounding. Achieving an output likely ten times that of his better-known contemporary, Hokusai, three times that of A. Hiroshige, it may be he was as much a servant to the effort (like a queen bee laying eggs for a large bee-hive), as a creator of it. A practicing Buddhist, Kunisada's fertile mind may have been his inner nature, his imagination endlessly inventing new dynamic compositions, dramatic portrayals, and original uses of patterns and color. It is the formal quality of Kunisada's prints, his sense of pictorial structure and dramatic development, that I am most eager to display and share.

I have noticed my enjoyment of the prints increasing as I learn the stories of the material depicted. For this reason I have endeavored to learn the stories of the plays, the roles, and the actors. I am especially indebted to the work and interest of Kim Meredith of Thetford, VT in this pursuit.

I would also like to thank my friend Taylor McNeil for his loan of several wonderful Kunisada prints, depictions of Danjuro VIII, for this exhibit. Taylor hosts a Twitter account featuring Kunisada's prints and you might enjoy taking a look.

All three of us hope you enjoy this little insight into the wonderful art this artist Kunisada has to share!

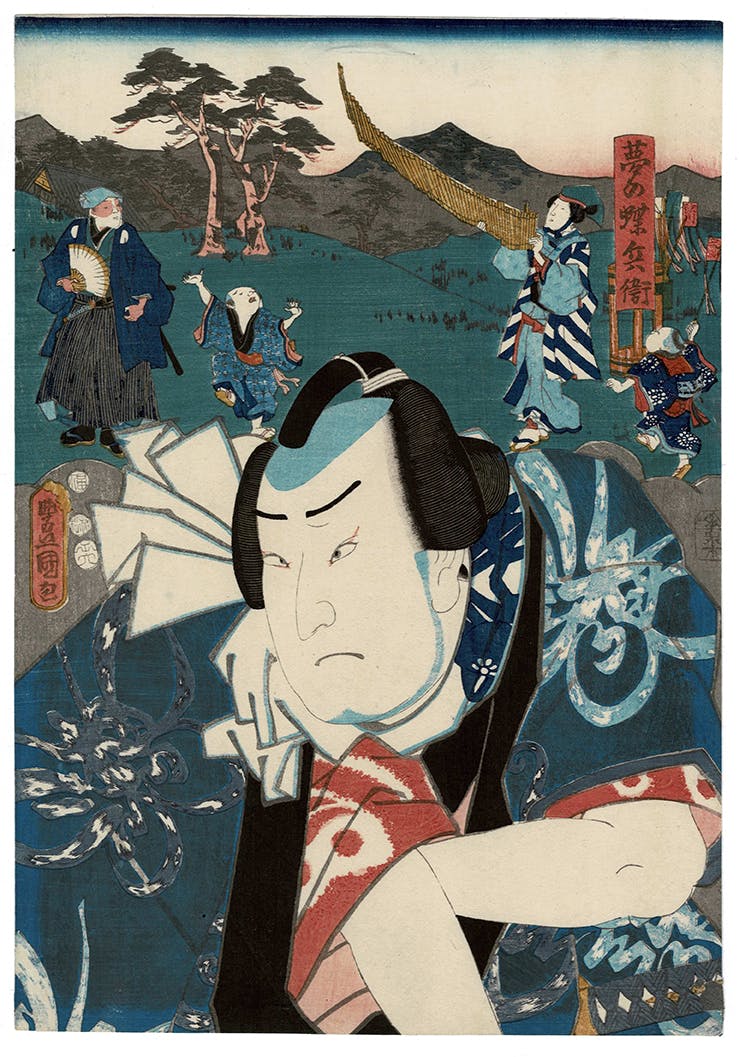

Shibaraku! (Stop a Moment!)

Shibaraku is a kabuki “short", a single scene performed alongside other dramas, a kabuki dance piece historically connected to the Danjuro lineage. In this exhibit it is not one of our five plays, it is our little “short", our introduction.

Danjuro I is credited as the author of “Shibaraku", Danjuro V (1741 - 1806) and Danjuro VII (1791 - 1859) both built the role to make it famous. The story? The evil Kiyohara no Takehira is usurping power and about to take the lives of several of the Imperial family when, at the last possible instant, the character of Kamakura Gongorō Kagemasa, marching down the hanamachi (a long platform gangway leading to the main stage, stage right), calls out: “Shibaraku"! Using dance moves and spoken words Gongorō defeats Takehira and his warrior followers. The drama got its title organically when, in an early performance of 1697, Danjuro I yelled out “Shibaraku (stop a moment)!" when fellow actors on stage overlooked his entrance cue.

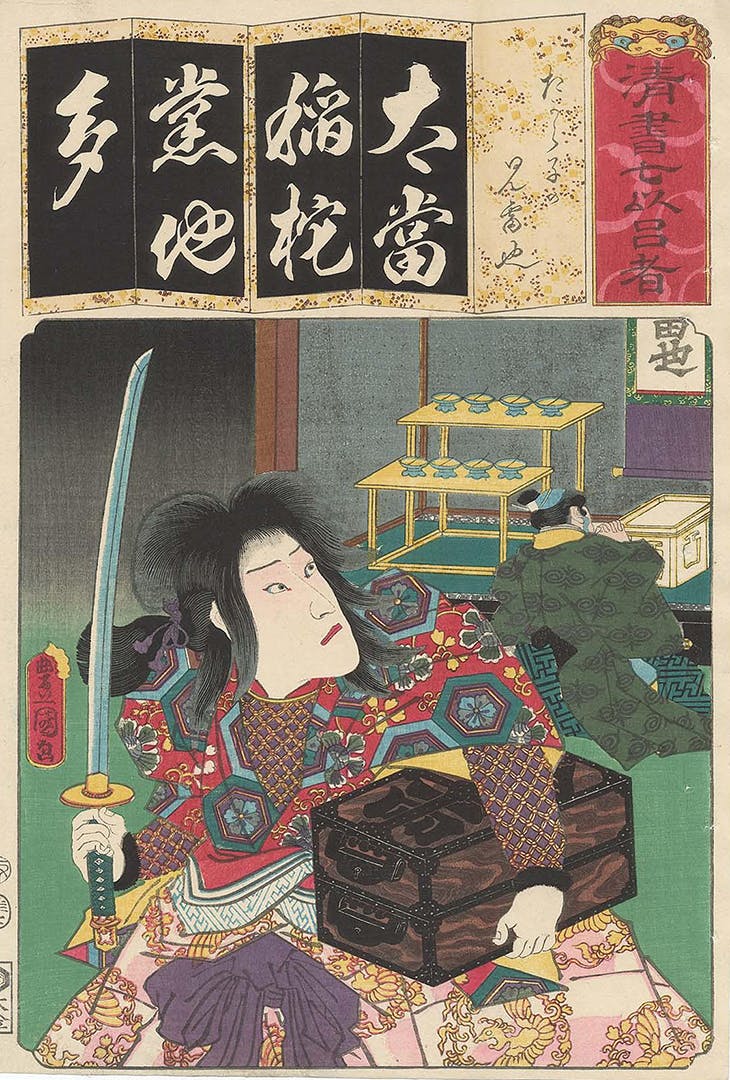

1. Jiraiya Gôketsu Monogatari (Tales of the Gallant Jiraiya)

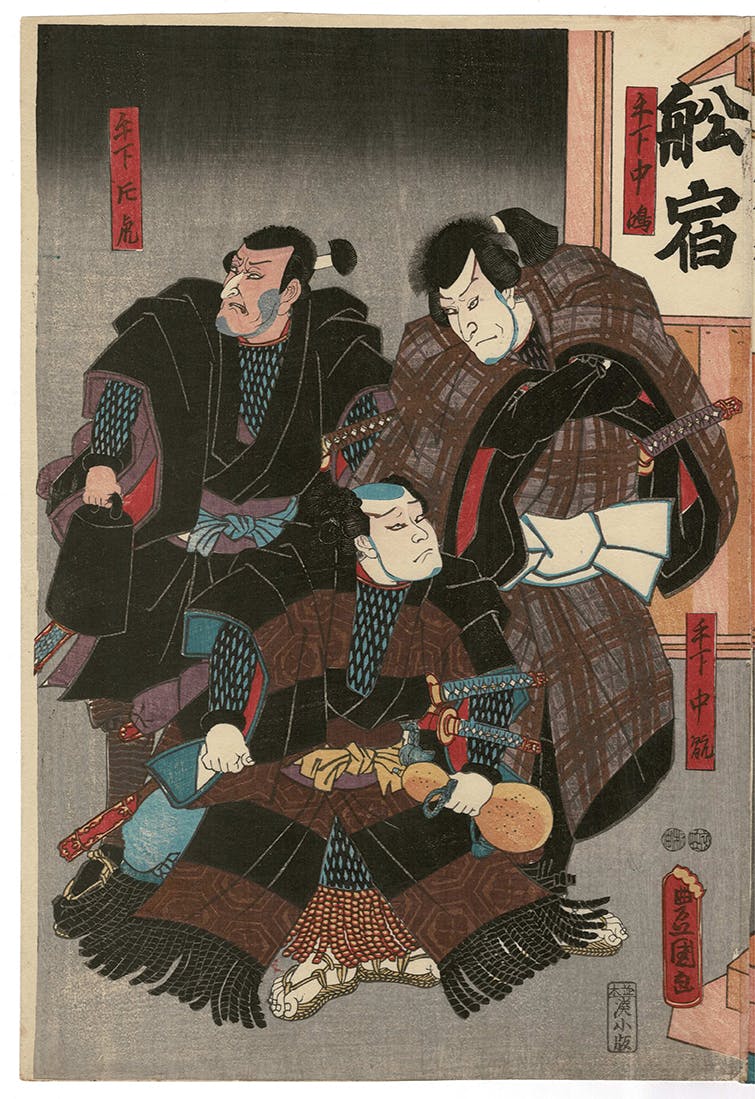

“Jiraiya Gôketsu Monogatari" was first developed as a series of novels (1839 - 1868) for which Kunisada made numerous illustrations. Kawatake Mokuami wrote the story into a play which premiered to great success in July, 1852 at the Kawarasakiza Theater in Edo with Danjuro VIII as Jiraiya, Iwai Kumesaburo III as Tsunate-Hime (in disguise as Princess Tagoto-Hime), and Arashi Rikan III as Orochimaru, the central villain character possessed of an evil serpent that has emerged from a deep hibernation to obliterate humanity. The character of Jiraiya continues today in the form of anime cartoon films and has inspired at least one Pokemon character, Froakie. In 1975 “Jiraiya Gôketsu Monogatari" was revived in a production at the National Theater, and the character of Jiraiya also lives on in anime cartoon form (in the “Naruto" manga series created by Masashi Kishimoto). It is currently being re-enacted in the arena of US national politics with Rep. Jaime Raskin playing the role of Jiraiya, Rep. Liz Cheney the role of Tsunate-Hime, and former president Donald Trump in the role of Orochimaru, or perhaps more accurately in the role of the evil serpent with characters such as Kevin McCarthy playing the role of Orochimaru.

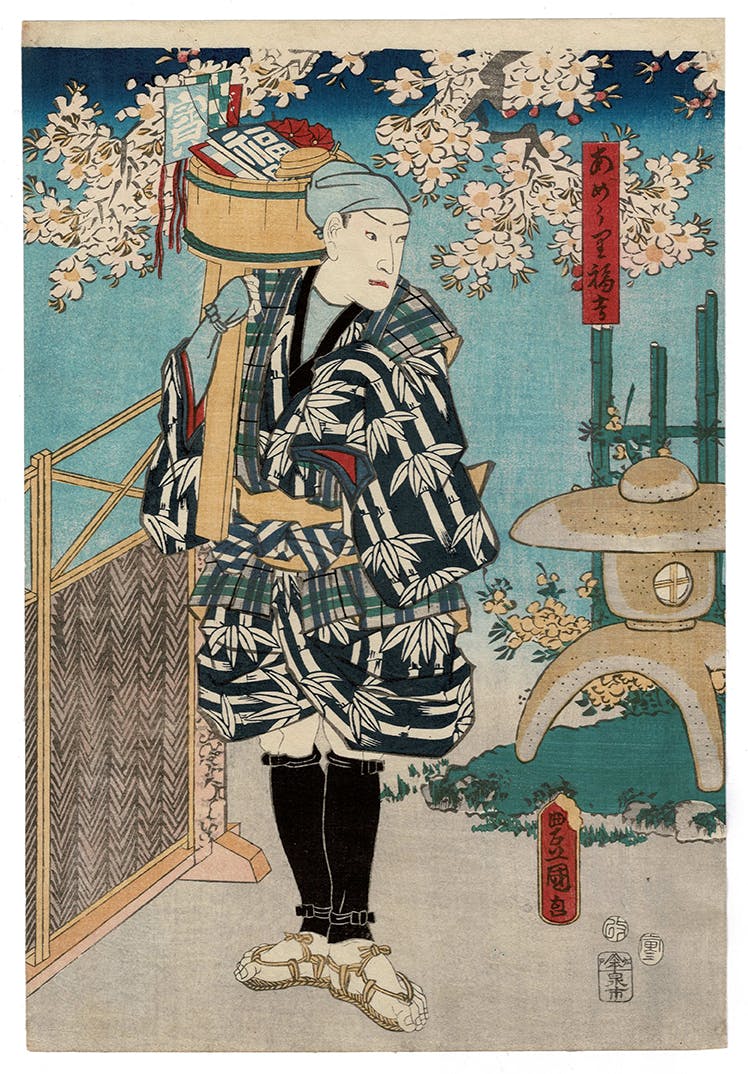

2. Godairiki Koi no Fûjime (Five Great Powers of Love)

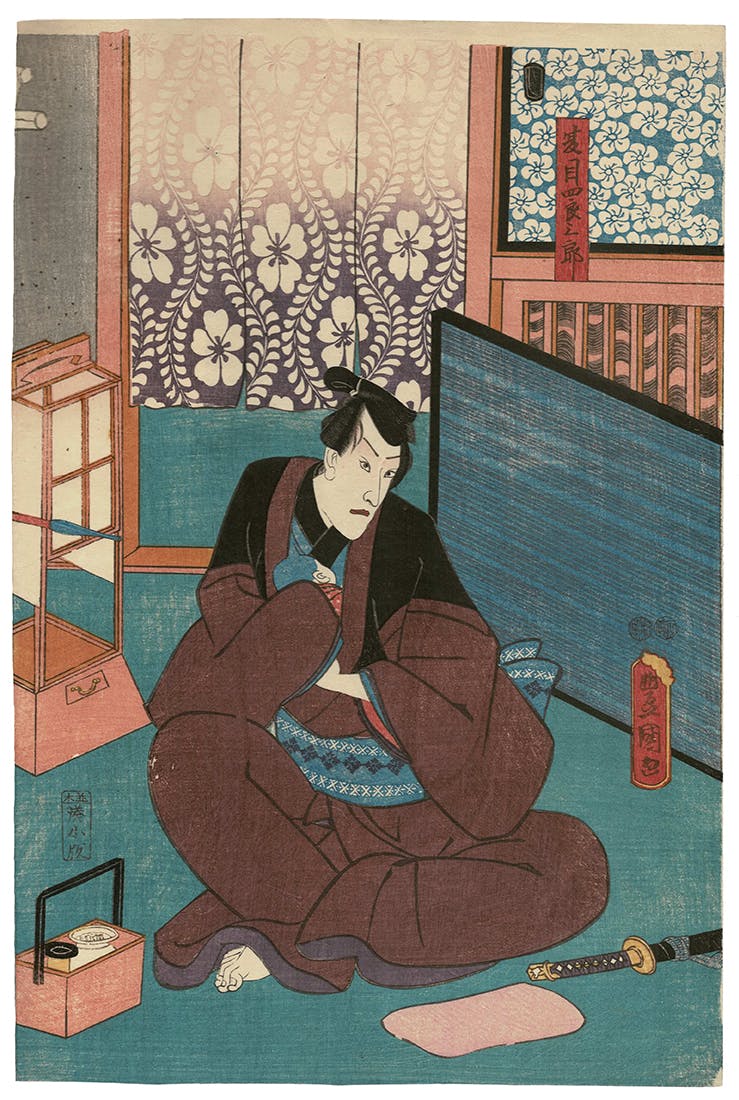

Godairiki Koi no Fûjime centers around a love triangle between Satsuma Gengobê (hero of the play), his lover Sakuraya Koman (a geisha), and Sasano Sangobê (the villain). Koman has shown her love for Gengobe by cutting off her little pinkie finger, but still Gengobê has room for doubt and jealousy.

Sasano Sangobê, who at one time had made advances of his own to Koman, tricks her into writing a letter pretending to sever her relationship with Gengobê. After finding the letter, forged by Sangobê to be in Koman's hand and describing her love for Sangobe, Gengobe becomes convinced Koman is unfaithful. Gengobe notices that the word godairiki, which Koman had once written for him on her shamisen, has been rewritten to look like a similar pledge to Sangobê. He murders Koman (oh dear!) and then, later learning he had been tricked, kills Sangobe. The play ends with some recompense. Gengobei is able to return a family treasure stolen by Sangobe. An odd ending, to be sure.

The play appears to be a re-work of an earlier story (published by Ihara Saikaku in 1686 about a fellow named Gengobei who comes from Satsuma, a remote area of Japan, and a woman named Oman. Translated into English by Wm. Theodore de Bary as Five Women Who Loved Love (Rutland, Vermont, 1956), this story is more interesting, more investigative about the nature of love, and ends on a much happier note.

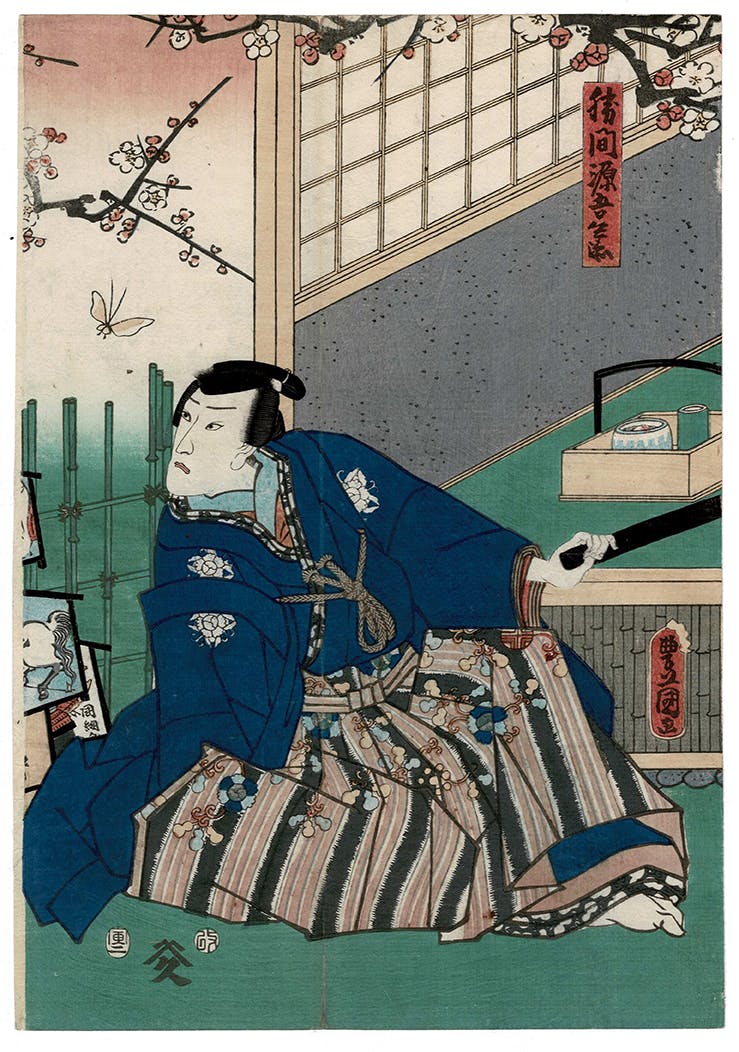

3. Genji Moyô Furisode Hinagata (A Rustic Genji)

The Tale of Genji originated as an 11th century novel written by Lady Murasaki Shikibu, who worked at the Imperial Heian court. In the 1820's Kunisada collaborated with author Ryūtei Tanehiko (1783 – 1842) in the publication of an updated version of the tale: “A Fraudulent Murasaki’s Rustic Genji" by Ryūtei Tanehiko, 1829–1842), set in the 15th century. The plot of this updated version revolves around the adventures of Ashikaga Mitsuuji, second son of Ashikaga Yoshimasa, who haunts the pleasure quarters of Edo (instead of the Heian court of the original tale). Mitsuuji seeks a stolen sword, mirror, and poem, (somehow these treasures need to be found to restore the stability of Japan). While on his pursuit Mitsuuji seduces many women, has children by several of them, and though seemingly an endless philanderer always seems to come out on fine, like the original Prince Genji, fortunate and transcendent, as do his lovers and offspring.

Kunisada's illustrations for the book (which was produced in a series over 13 years) became a source for numerous single sheet print projects, many of which accompanied theater productions of the Genji story (Genji Moyô Furisode Hinagata).

4. Imoseyama Onna Teikin (Adventures of Eboshiori Motome)

This play revolves around a love triangle between Motome, a disguised Princess Tachibana (sister to the villain, Soga no Iruka, who is attempting to overthrow the Emperor) and Omiwa, who lives next door to where Motome is living (Motome is living in hiding, seeking to avoid apprehension by Soga no Iruka).

The print depicts the 3rd scene of Act IV: “The Spool of Love Travel Dance" (Michiyuki Koi no Odamaki). Danjuro VIII, in the role of Motome, attaches a spool of red thread to Princess Tachibana's kimono to be able to follow her home following a night-time visit. Omiwa, Motome's lover, does the same, attaching a spool of white thread so she can follow Motome. All three end up at the palace of Iruka, and its then that the sparks fly. Omiwa loses her life, but somehow gains immortality by supplying blood which, in a convoluted way we can't figure out, allows for the overthrow of Iruka and his grasp on power. (More research needs to be done on this story, for sure.)