Kunisada and the Chushingura

Stories of Mob Violence and Politics, Theater and Art.

February 5, 2021 - April 10, 2021

Chushingura, Japan’s most popular kabuki play, finds the origin of its story in an event of organized mob violence in 1702. This exhibit of woodblock prints depicting imagery from 19th century productions of the play is motivated by a notion to use stories of that play to better understand a recent event: the 2021 storming of the U.S. Capitol. Blind loyalty, desires for vengeance, secretive scheming exciting illegal violent group action, I see parallels between the Jan. 6 event and Chushingura. This effort doesn’t intend to equate the Proud Boys or the Oath Keepers with the 47 rōnin (“The Loyal Retainers”) of Japan. My idea is to use Kunisada’s Chushingura art to gain insight into motives and characteristics of violent group action.

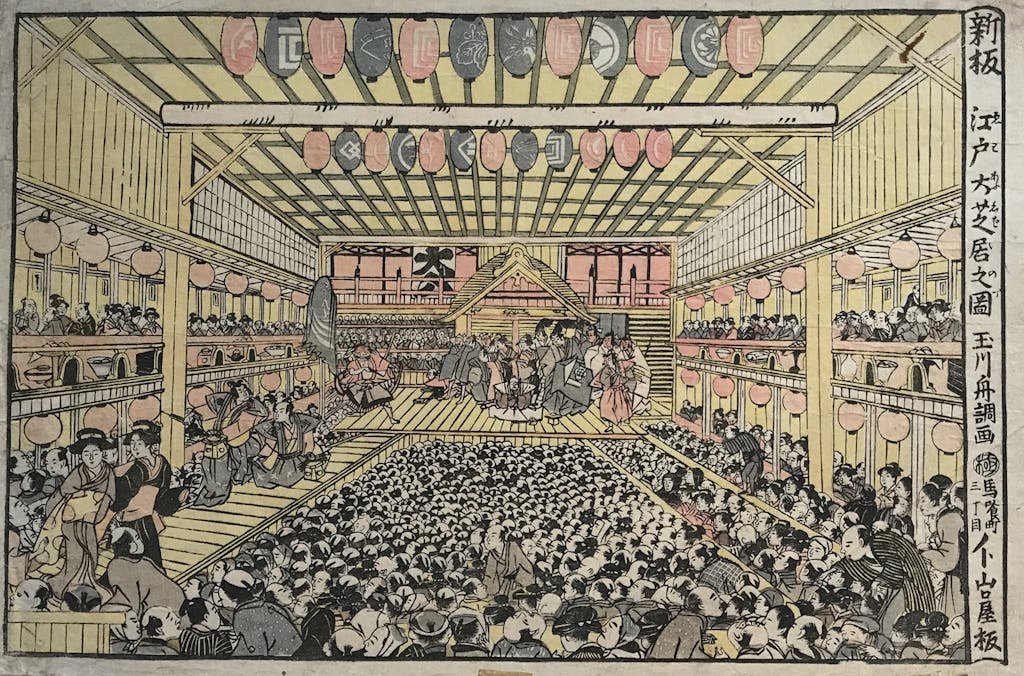

Chushingura is a complex story of unquestioning loyalty, revenge, conflict, love, and punishment developed from the Ako incident which took place in Edo (modern day Tokyo) in 1702. Initial performances featuring this incident were forbidden by the ruling Tokugawa shogunate. In 1748 Chushingura escaped censure as a puppet performance in Osaka set in an 13th century time period with changed identities. The puppet play was transformed to kabuki and eventually grew into a cultural phenomena about which has been said: “if you study Chûshingura long enough, you will understand everything about the Japanese.” (H.D. Smith, Columbia Univ., 1990)

I experienced an update to the exhibit when last Saturday a visitor to the gallery shared her recent experience listening to a podcast. “I think it might have been about this story, something about 47 rōnin committing seppuku in the early 1700's. Super crazy stuff." The podcast is indeed a fascinating investigation into the original Ako incident and reveals information and research I had never before found. It mentions the various plays, art, controversy and legend that arose from the incident but sticks to the history. It doesn't explore the Chushingura play or indeed ever mention the name Chushingura, the term used for the play and for the ukiyo-e art depicting the story of the 47 rōnin.

Find the “History this week" podcast, “Revenge of the Ronin", here.

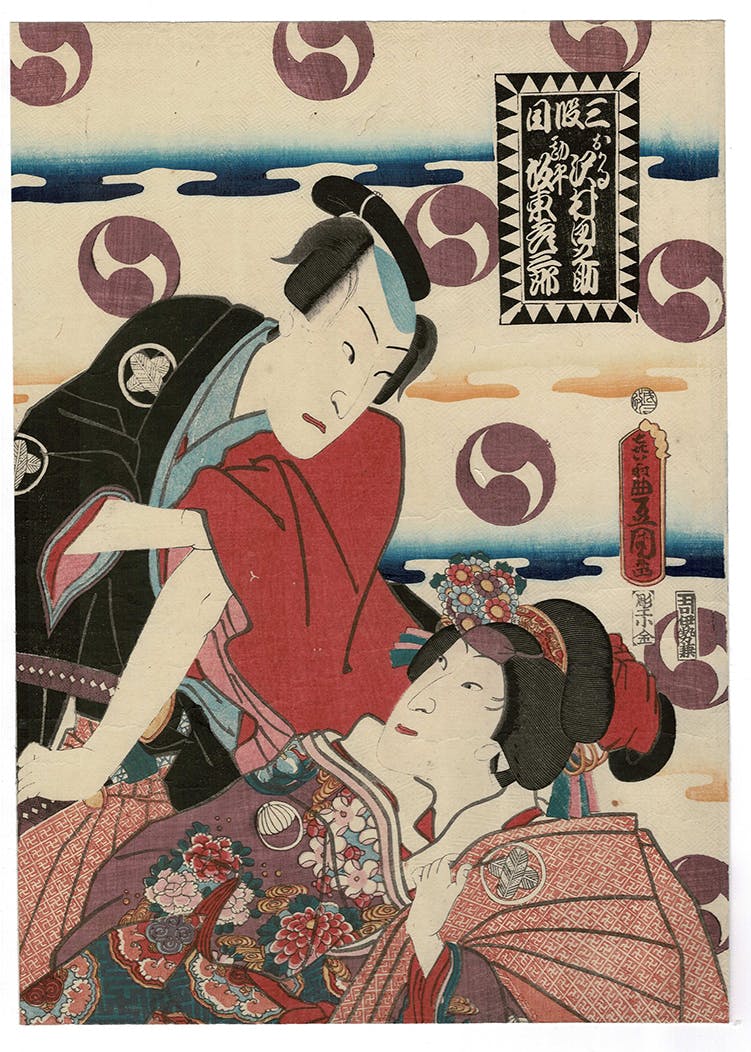

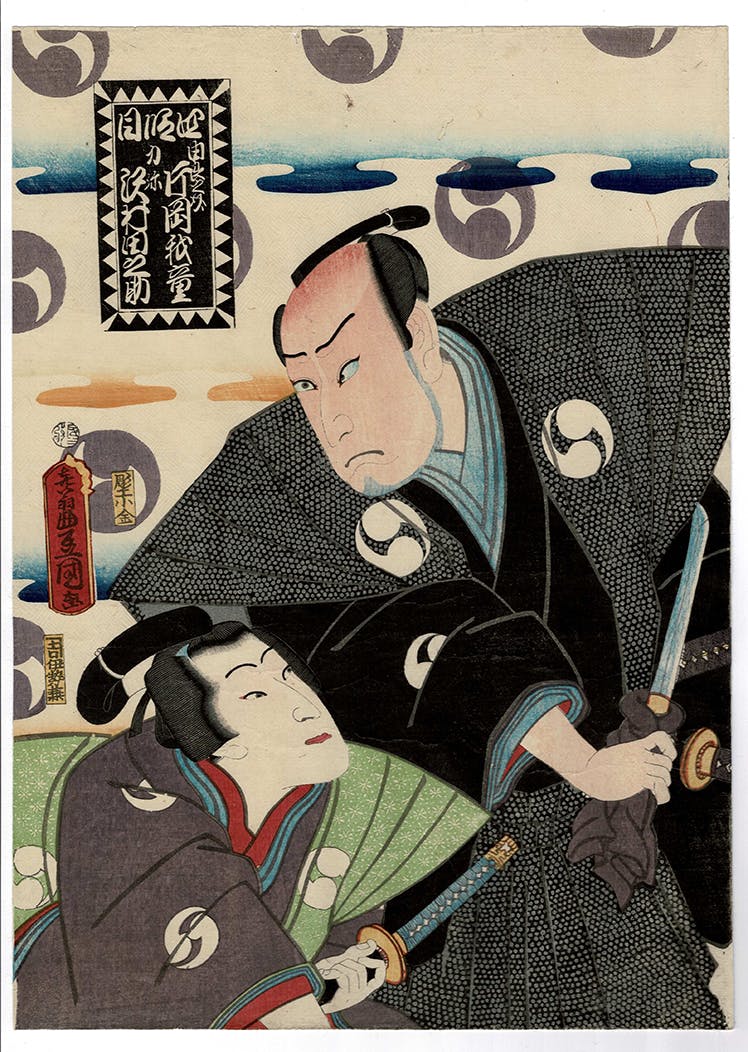

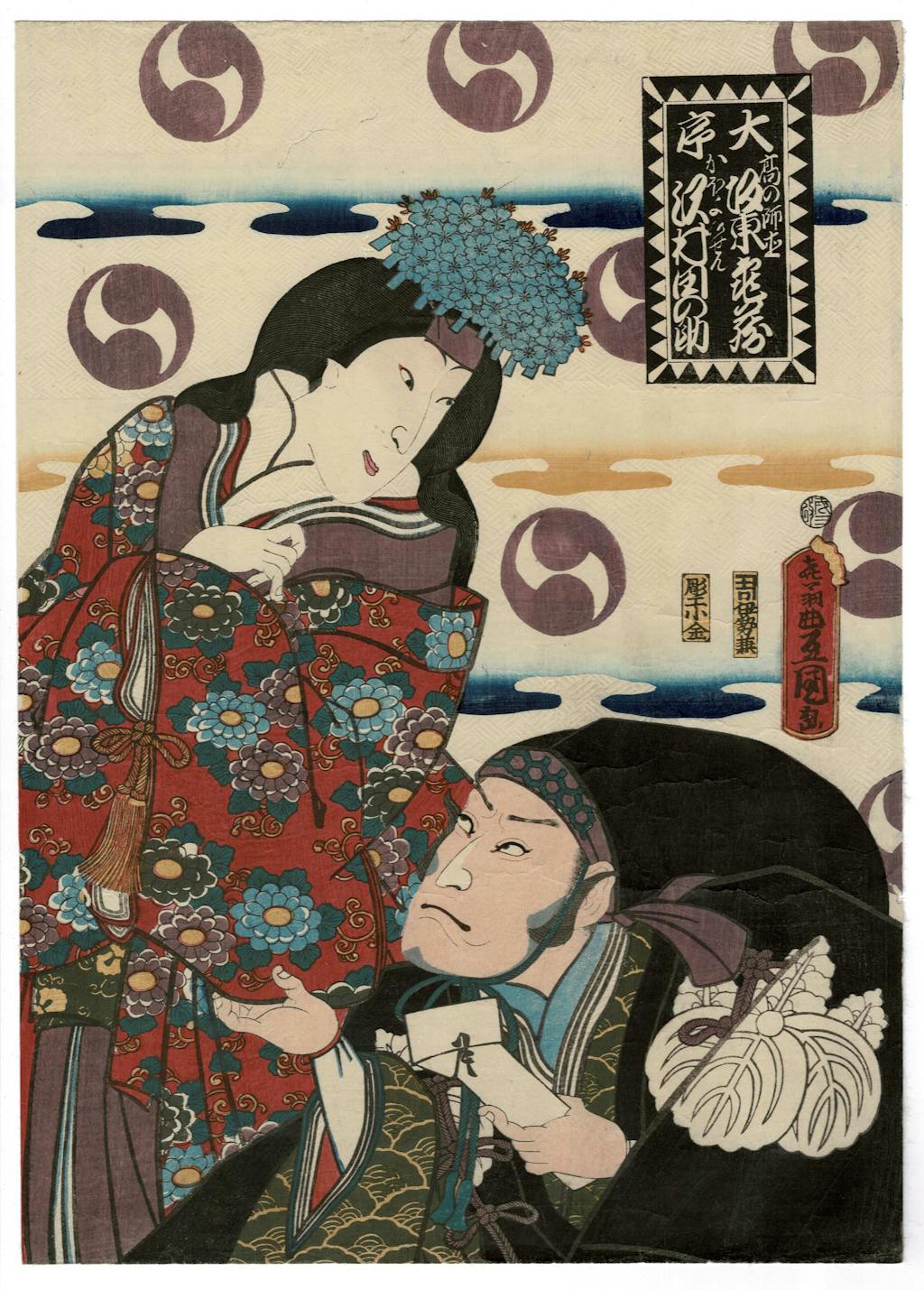

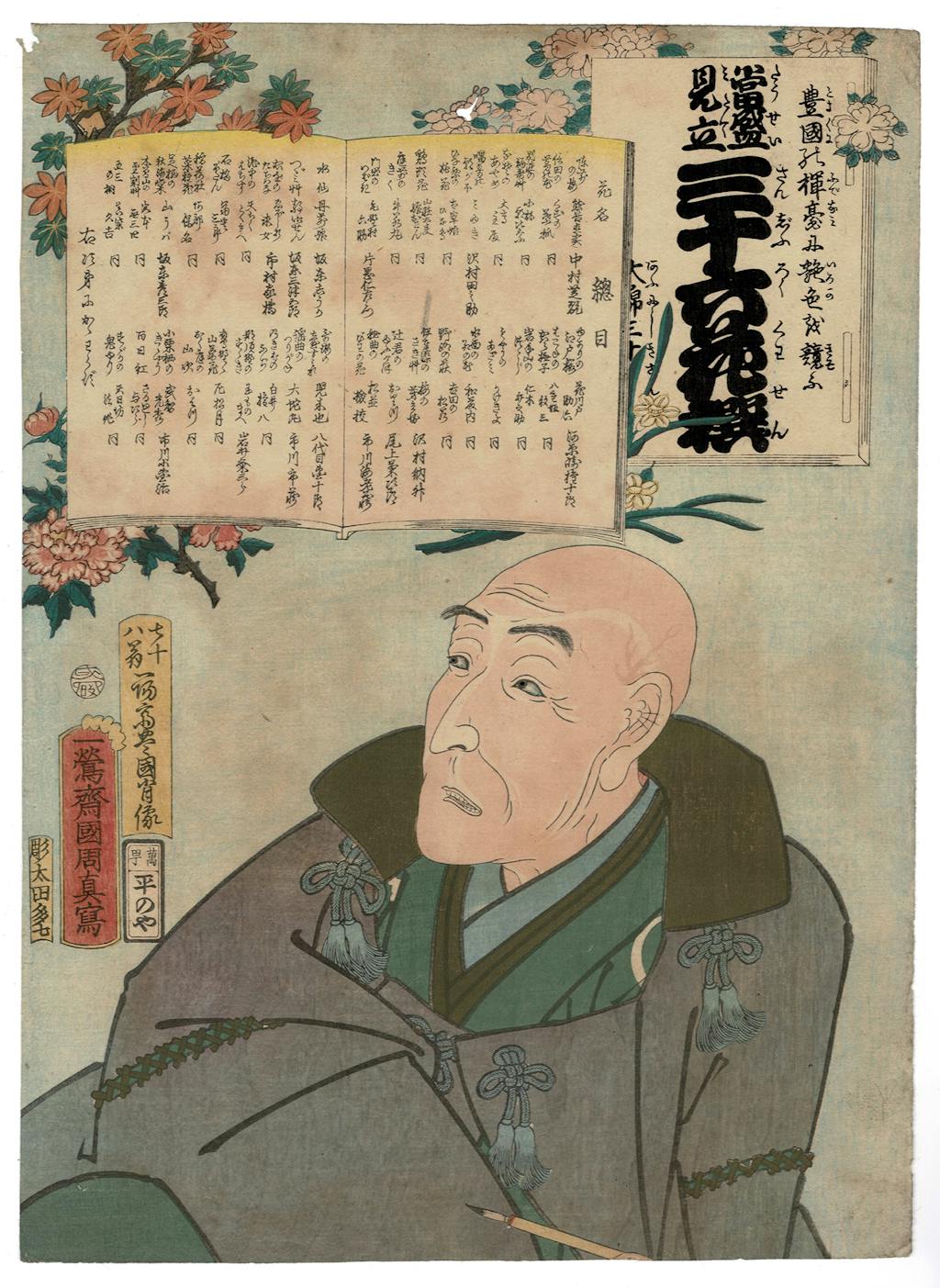

Utagawa Kunisada (also known as Toyokuni III), was recognized in his lifetime as Japan’s most successful and prolific ukiyo-e artist. Kunisada dominated the field of yakusha-e (kabuki actor prints), and he designed hundreds of prints depicting Chushingura scenes and actors. In Kunisada’s Chushingura prints are themes characteristic of his art: emphasis on movement and drama, a focus on tensions in depicted human interactions, strong formal arrangements with masterful use of pattern and color to develop dramatic pictorial spaces. The MBFA exhibit explores Kunisada’s beautiful narrative and character portrayal; it also attempts to use this art to better understand aspects of the recent event of the storming of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC.

I sense these insights:

- When you feel you have lost something significant the drive to seek revenge is compelling.

- Blind loyalty to a person or cause is an appealing path to pursue when you are unemployed, master-less, and feeling you have little to lose.

- The tendency to choose a path of drama over reason in our human interactions, especially in politics, is powerful.

- Symbols gain importance in the context of this human drama when that drama is chaotic. Mons and other symbols of the cause of the 47 rōnin loom large in Kunisada's Chushingura prints. Red MAGA hats and Trump flags are a noteworthy presence in video footage from Jan. 6, 2021.

I hope you enjoy your time with this effort of mine. Is Chushingura nutty drama? Yes. Were the 47 rōnin honorable in their efforts? Hmmmm. Did Kunisada believe strongly in their cause? I am thinking maybe not. But in appreciating this violent story of a culture we know little about, we might juxtapose its long-lasting popularity with another fact: Japan boasts the lowest murder rate of any country in the world. Theater and art can play a role in channeling our need for drama, our instinct for revenge, our attraction to blind loyalties and conflict, our obsession with expressions of power.

Note 1: The exhibit includes the addition of numerous prints new to the MBFA collection since a previous Chushingura exhibit in 2019.

Note 2: The digital images presented in this online exhibit are all from prints that are part of the real exhibit at the MBFA gallery in Lyme.

Come see them on Fridays or Saturdays through April 10.

I predict this online exhibit to evolve past its opening date of Feb. 5.

Check back for updates!

Note 3: Set up a timeline between 1702, the date of the Ako incident, and today. You'll notice these prints date from a midpoint between those two dates. This fact may help in imagining a context for this exhibit.

Note 4: These prints are made using the Japanese hanga method, the same technique I use to make my own art. Printed from separate carved blocks using brushes and a hand-held baren as a press, this printmaking represents an intimate and complex handcraft. I am fascinated by what it took to make them: multiple teams each pursuing various parts of their manufacture. Publishers, involved also in sales and distribution, managed the production of the prints. They were likely sophisticated business people managing what was one of the largest industries in Edo (a city which at the time was among the largest cities in the world). Publishers worked with artists to develop the designs (Kunisada had numerous artists working with him in his design shop). These publishers utilized separate craftspeople, the block-cutters, to develop the blocks. They would have taken the design sheets from Kunisada's shop to the block-cutters. Block cutters utilized impressive carving skills to interpret the drawn lines of the artist(s). Those fine strands of hair and the delicate kanji labeling? They were all carved from cherry wood blocks. Publishers then would have taken the blocks to the print shops which employed printers working seated at low benches. Using for materials only paper, water, rice paste, and pigments, and for tools just brushes and barens, the printing was done entirely by hand, block by block, color by color, sheet by sheet. These printers would, likely with color input from Kunisada himself or some of his assistants, make, dry, and trim the prints to return to the publishers ready for sale. The prints include censor's seals and labeling to indicate the various makers of the print, the designer, the block-cutter, the printer and the publisher along with indications of the print's story: the play, the character portrayed, the series it was part of and more. Actor's names, interestingly, were for much of the period forbidden to be shown on the prints.

The fact these prints are available 160 years later at affordable prices I find astounding. Demand for Japanese prints today is high, but great also is the supply. Kunisada likely designed over 20,000 prints during his 55 year career. I am fascinated by his vision, his ability to endlessly innovate in the creation of this prodigious quantity of art. A guess as to the total number of his prints that were made? My guess is perhaps 6 million. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has in its collection over 10,000 prints designed by Kunisada. Imagine!

Note 5: I am fascinated by Kunisada's vision and his ability to endlessly innovate in the creation of such a prodigious quantity of art, even weighing in on subjects carrying political and societal implications. I am super pleased to be able to share this fascination in this exhibit, both at the gallery in Lyme and online.

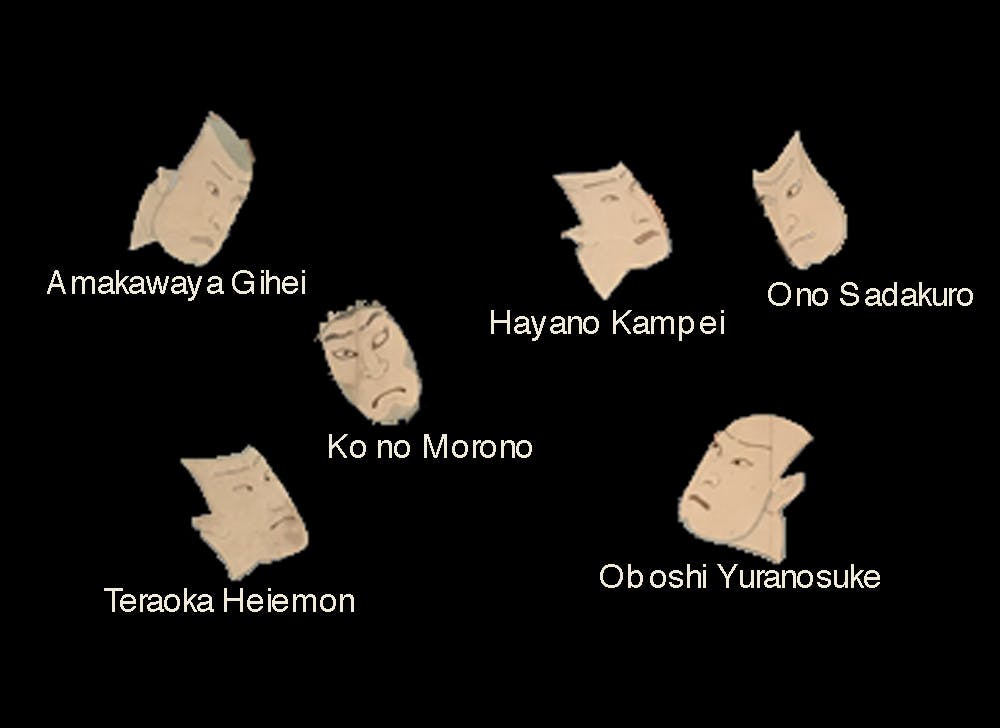

Factions of the Chushingura

See above the mon (family crest) of the Tokugawa shogunate, the ruling government established in 1600 following a century of civil war. Worked out as an image of a chrysanthemum, this mon is worn by Kira Yoshinaka (Ko no Morono in the play), the government official upon whom the 47 ronin seek revenge in Chushingira. A military dictatorship, the Tokugawa shogunate ruled Japan for its longest period of peace and prosperity. It was overthrown in 1868 (the Boshin War) by an alliance of powerful daimyo clans and the Emperor of Japan, whose house and lineage was reinstalled in 1868 as the Meiji Restoration. The rise of Chushingura popularity during the 19th century may parallel anti-Tokugawa sentiment. Integral to the values of the new Meiji government (esp. an emphasis on blind loyalty), Chushingura enjoyed an apex of interest as propaganda for the militarism which culminates in Japan's participation in World War II. Chushingura was banned along with the American occupation in 1945, but an adviser to General Douglas MacArthur, Faubian Bowers, in 1947 advised the ban be lifted. Referred to as the savior of Kabuki theater, Bowers encouraged a production of Chushingura utilizing the most popular kabuki actors of the time. The play has grown in popularity since and has been performed and made into numerous movies, novels, and more in recent decades.

On the left is the mon (family crest) of Asano Naganori (Enyan Hangan in the play), the daimyo lord who, inside the palace of the shogun during an official visit, pulled his sword to attack Kira Yoshinaka (Ko no Morono in the play), the shogunate government official who becomes the target of the ronins' revenge.

On the right is the mon crest of the Wakanosuke clan. Hangan and Wakanosuke were friends and various of Wakanosuke's samurai followers are involved in the vendetta in Chushingura play.

In the middle is the symbol of the Asano rōnins. This image, something like a revolving yin and yang, is used by Kunisada and numerous other print designers of the middle of the 19th century to indicate imagery of the Chushingura. Print designers, Kunisada particularly, also used the image of jagged diagonals, in borders, in clothing patterns, in compositional arrangements, to indicate Chushingura imagery.

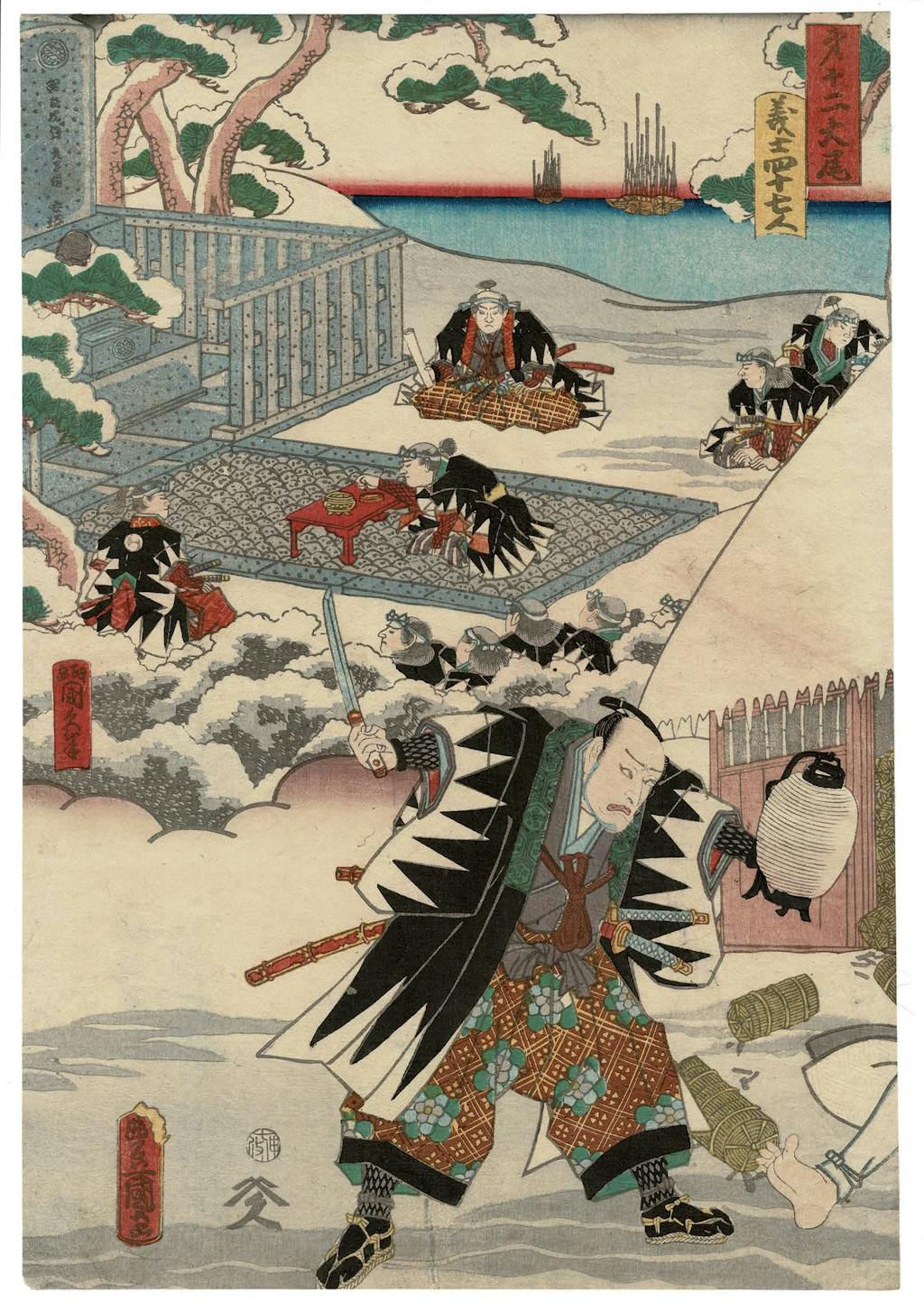

The facts of the actual historical event which took place in 1701/02 are murky. Asano Naganori (Enyan Hangan in the Chushingura) initiated a violent action of some sort against Kira Yoshinaka, a Tokugawa government official (Ko no Morono in the play), in the palace of the shogun during a state ceremony. This brought disaster to his house of Asano. For his misstep he was required to take his own life by seppuku (harikari, self disembowelment) that same day, lands and properties were confiscated, and his several hundred samurai followers became master-less unemployed men known as rōnin. The play revolves around the intrigue of 47 of these rōnin who chose to pursue a secret vendetta to finish the assassination their master initiated. Under the leadership of Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio (Oboshi Yuranosuke in the play) the intrigue climaxes with a night-time raid on the house of Kira on Dec. 14, 1702. The rōnin behead Kira, carry his head through the city of Edo to the Sengakuji temple where Asano's ashes had been interred, and turn themselves in. It seems there is popular support for the rōnin and it takes three weeks for the shogun to decide their fate. He requires, or offers, these rōnin the opportunity to take their own lives by honorable seppuku rather than be executed as common criminals. The 47 all commit seppuku and are currently interred in a set of revered graves at the Buddhist Sengakuji temple in Tokyo.

Wikipedia writes: “Though the revenge is often viewed as an act of loyalty, there had been a second goal, to re-establish the Asano's lordship and find a place for their fellow samurai to serve. Hundreds of samurai who had served under Asano had been left jobless, and many were unable to find employment, as they had served under a disgraced family. Many lived as farmers or did simple handicrafts to make ends meet. The revenge of the forty-seven rōnin cleared their names, and many of the unemployed samurai found jobs soon after the rōnin had been sentenced to their honorable end. Asano Daigaku Nagahiro, Naganori's younger brother and heir, was allowed by the Tokugawa shogunate to re-establish his name, though his territory was reduced to a tenth of the original."

It seems the folks who stormed our U.S. Capitol may enjoy no such redemption. But they may enjoy a place in our nation's history nevertheless. It may be our responses to the event bring new strengths to our government, and to our society, in ways we can't easily discern.

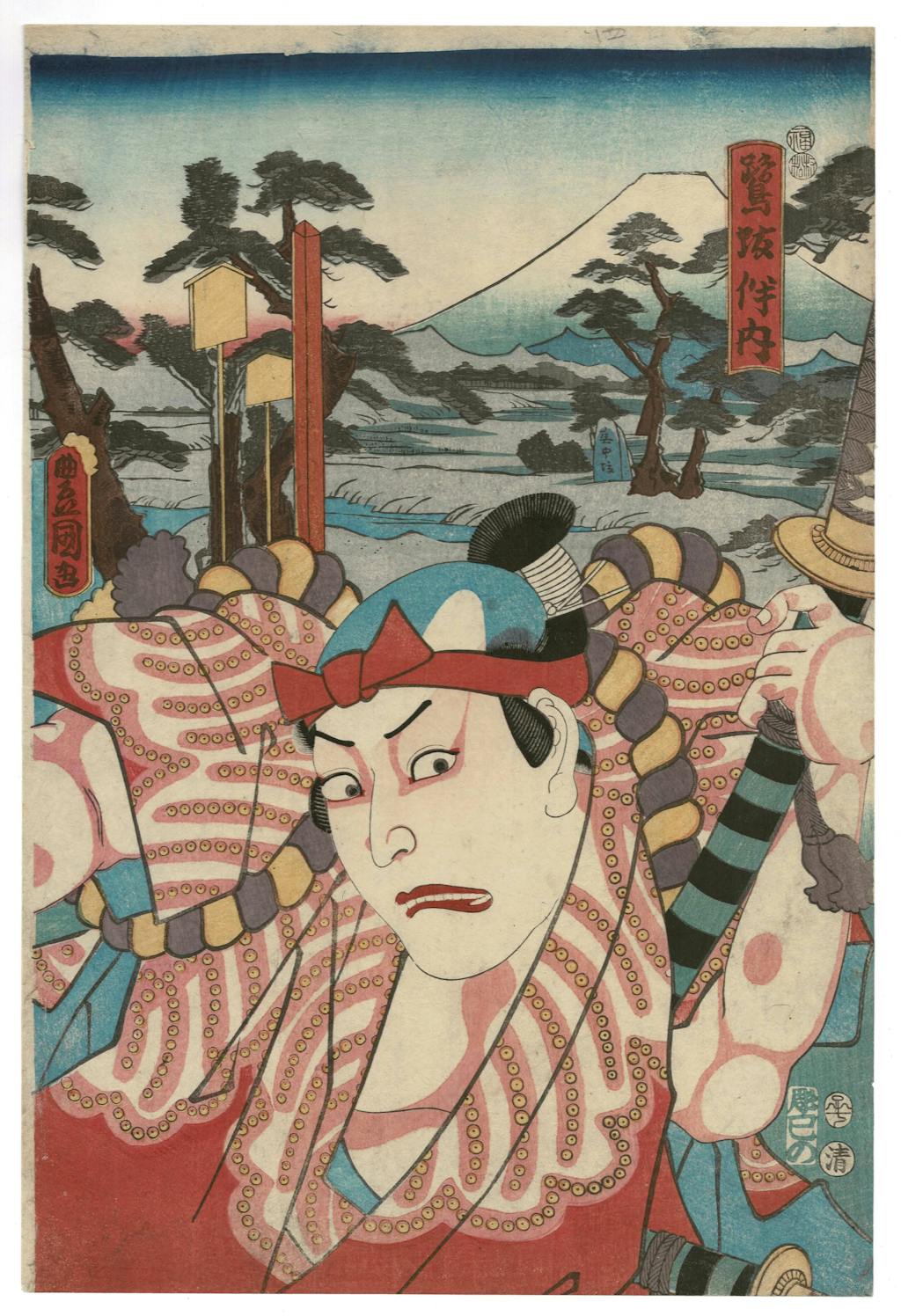

Men of the Chushingura

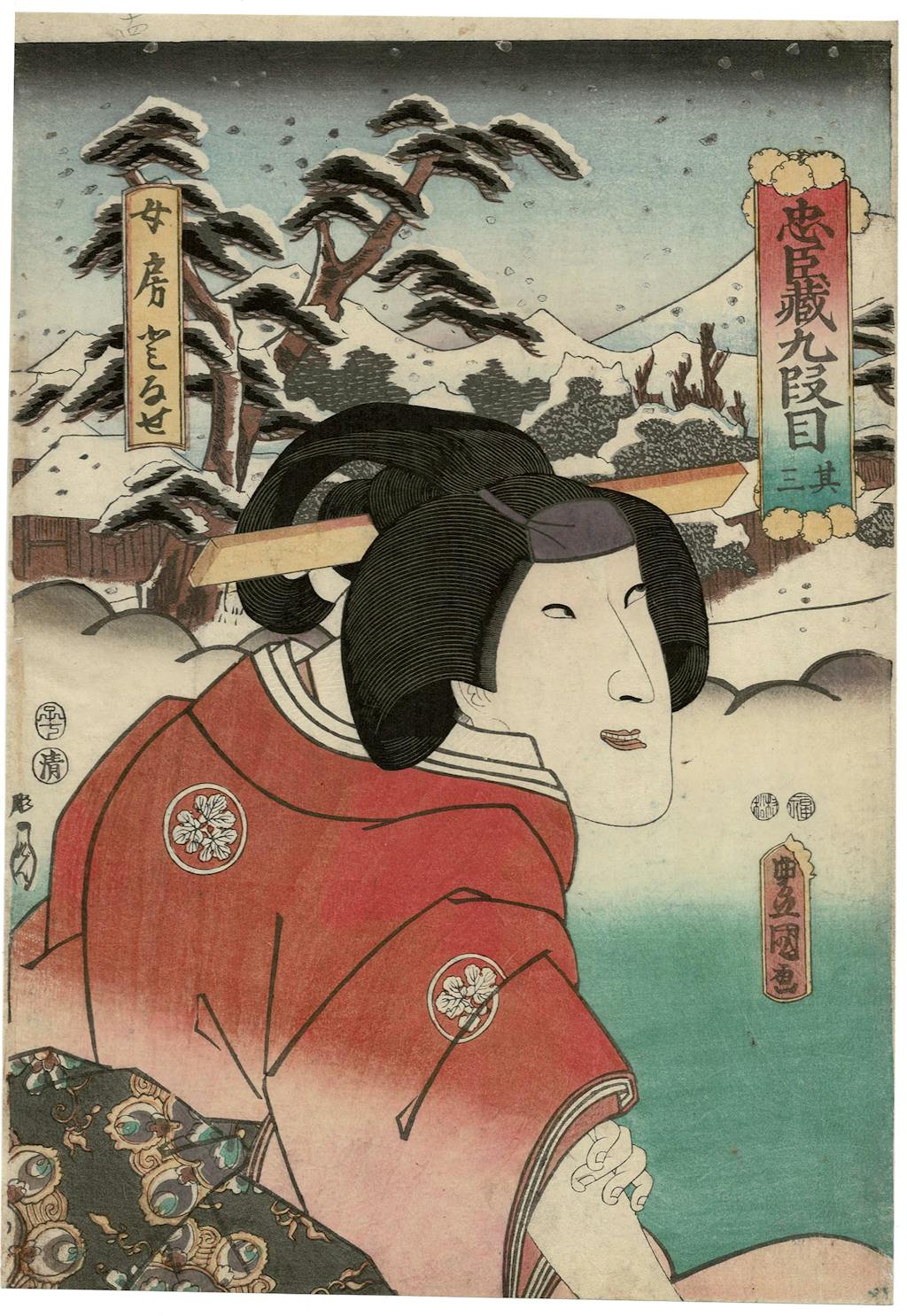

Women of the Chushingura

Couples of the Chushingura

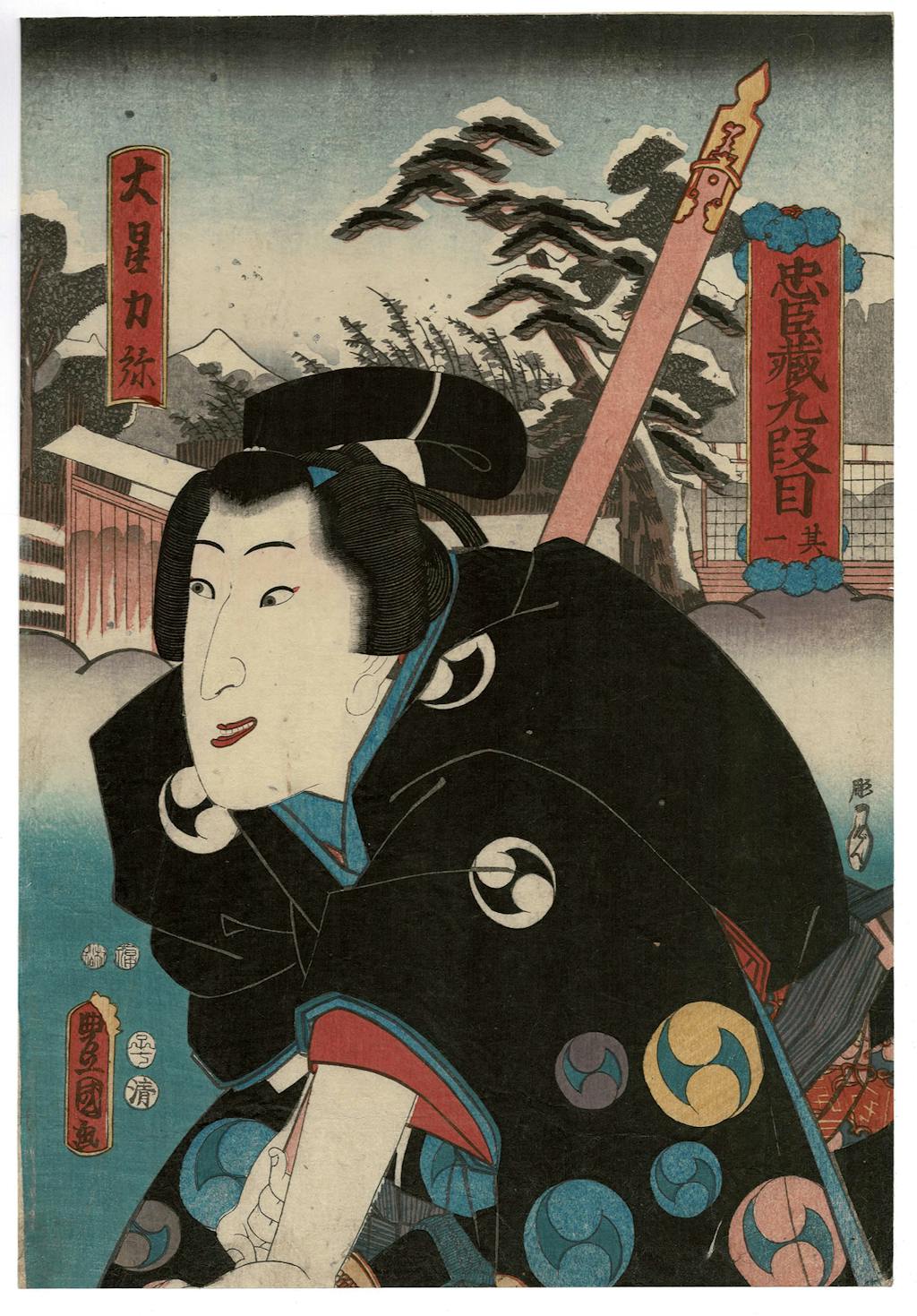

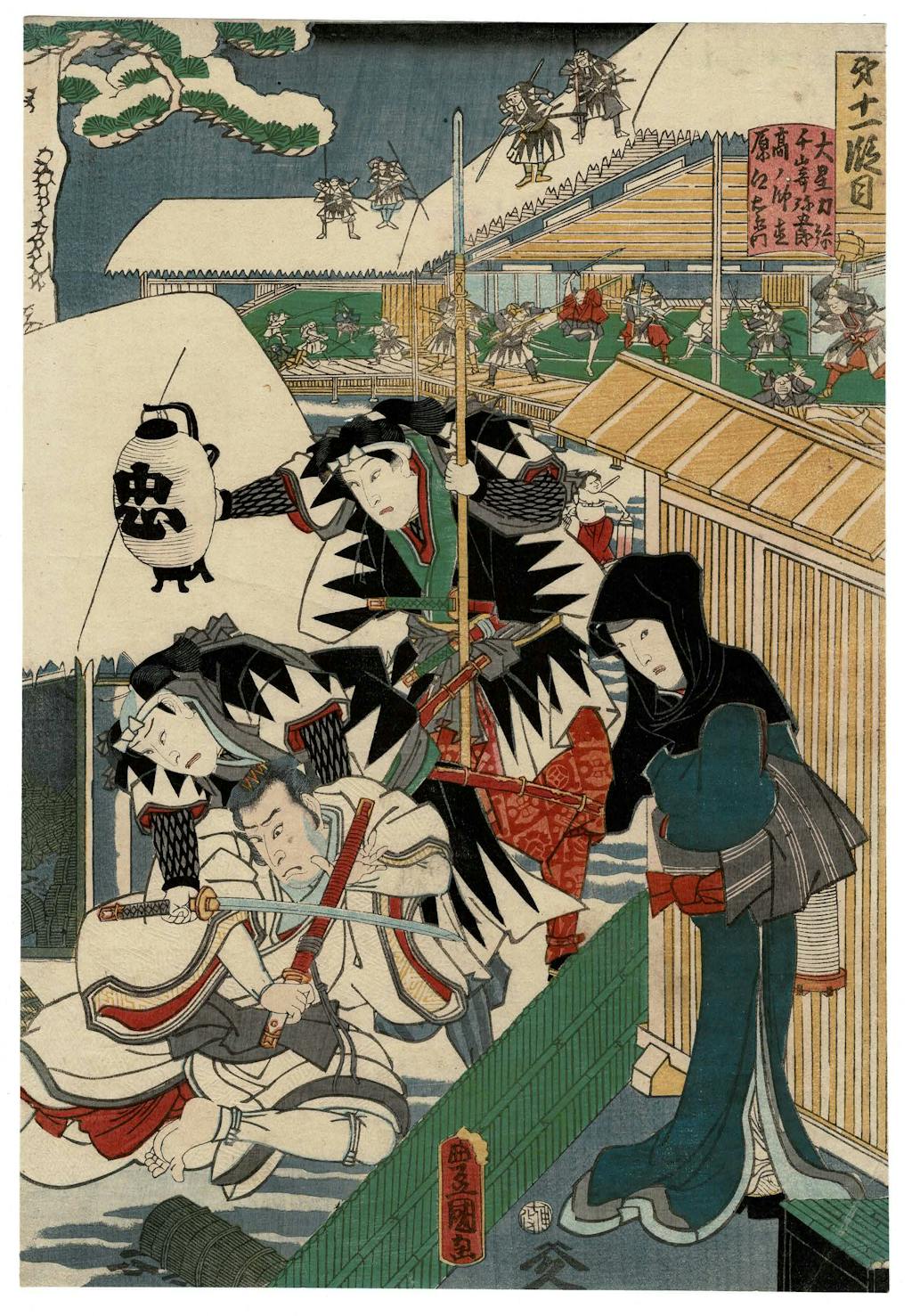

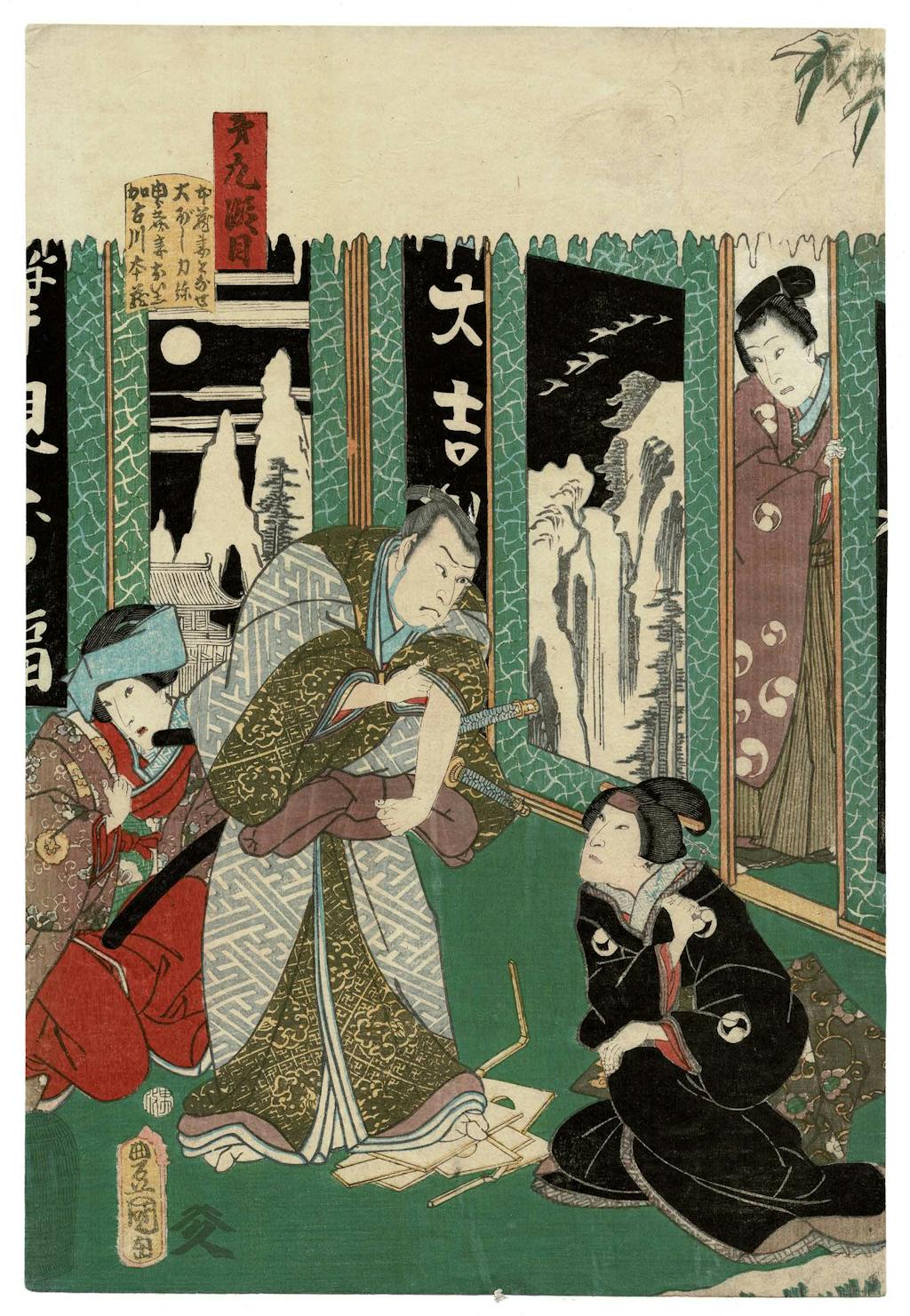

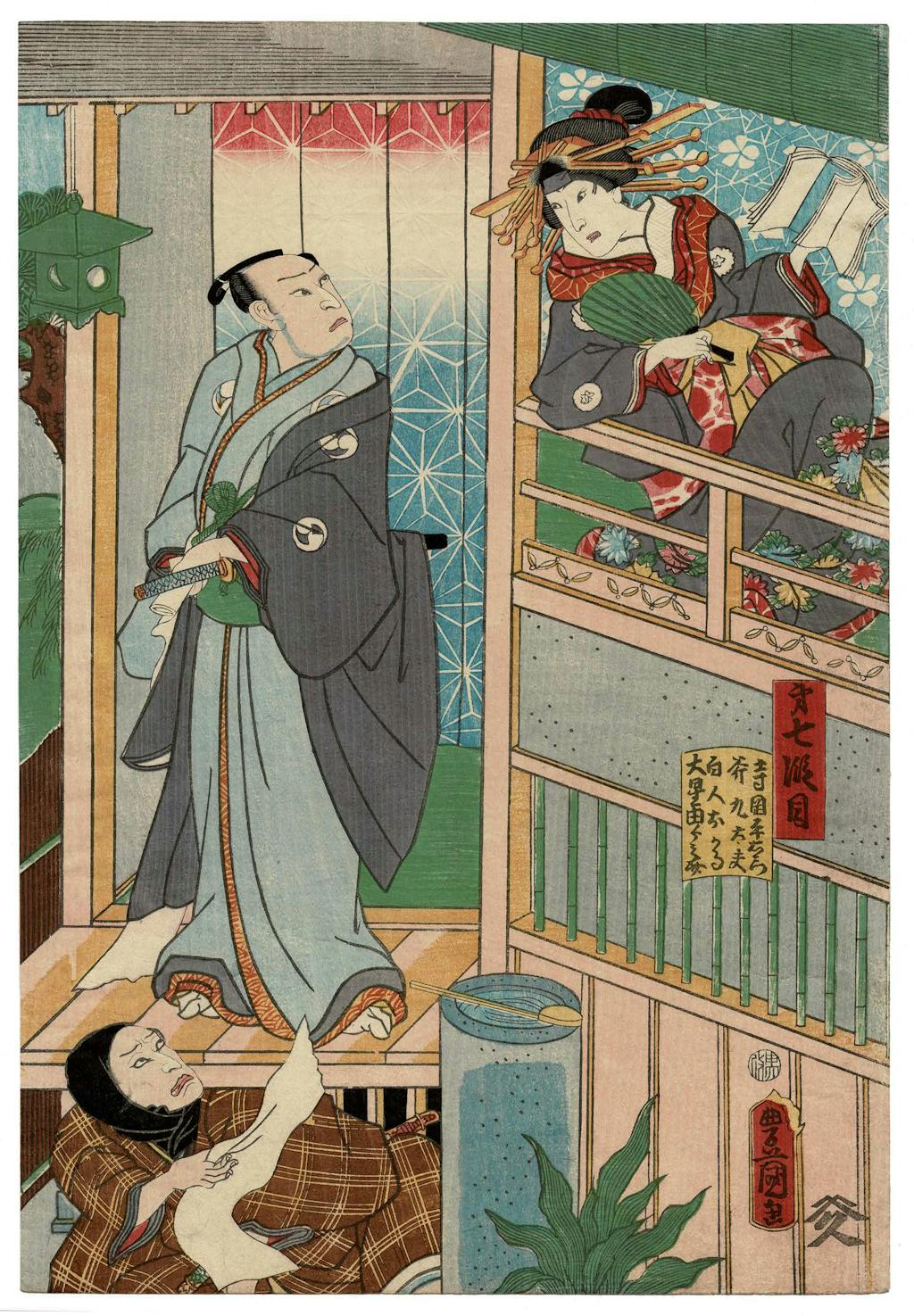

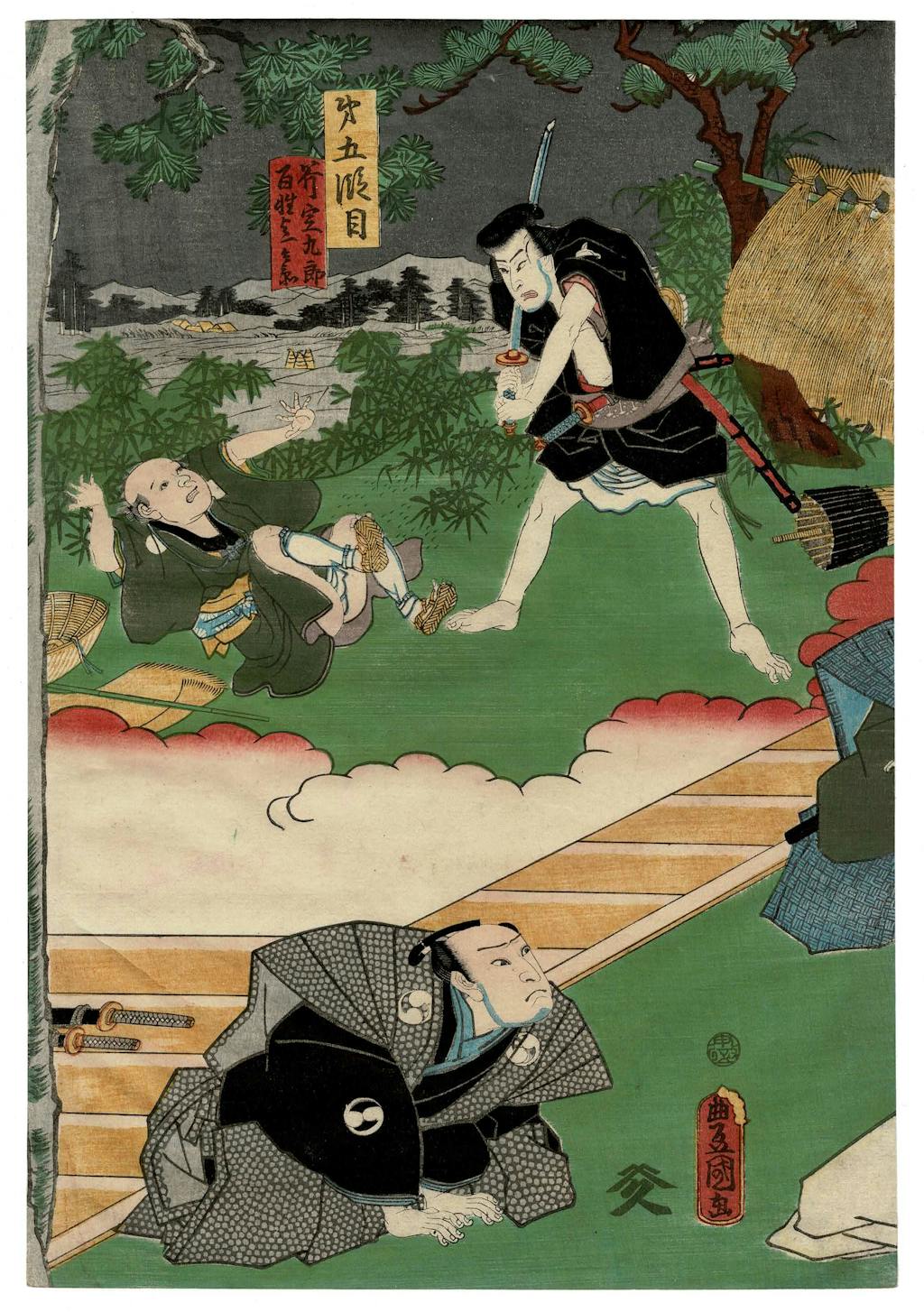

Events of the Chushingura (in eleven acts and twelve separate prints)

The exhibit's feature is a full narrative set of twelve prints, laid out as four triptychs, designed by Kunisada (after 1848 known as Toyokuni III) in 1860. Prints were made to depict particular actors in particular performances of Chushingura, and to depict the full narrative of the play. This is one of several full narrative sets that Kunisada designed over the course of his long career. Through the 19th century Chushingura became increasingly popular and relevant, the Confucian ideals of fierce loyalty it is built upon played into sentiments that eventually led to the restoration of the emperor of Japan and the end of the Tokuwawa shogunate.

The narrative is laid out to be viewed from right to left, so please scroll counter-clockwise to view.